This post is the inital post of a series I am going to be writing about the C++ features and the version differences. It will be mainly based on the textbook by Scott Meyers: Effective Modern C++. The book was published in 2015 which is before 2017. So that it doesn’t cover C++17 and mainly focuses on C++11 and C++14.

In this post I will be explaining fundamental concepts which will be used and further evaluated in the following posts.

Major C++ versions

| Abbr. | Version |

|---|---|

| C++98 | first edition |

| C++03 | second edition |

| C++11 | third edition |

| C++14 | fourth edition |

| C++17 | fifth edition |

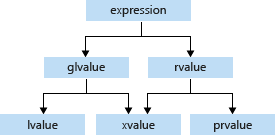

RValue - LValue

If you can take the address of the expression then it is LVALUE; if not, then it is RVALUE. (Generally)

Microsoft Documents states the difference as follows:

An lvalue has an address that your program can access. Examples of lvalue expressions include variable names, including const variables, array elements, function calls that return an lvalue reference, bit-fields, unions, and class members.

A prvalue expression has no address that is accessible by your program. Examples of prvalue expressions include literals, function calls that return a non-reference type, and temporary objects that are created during expression evalution but accessible only by the compiler.

An xvalue expression has an address that no longer accessible by your program but can be used to initialize an rvalue reference, which provides access to the expression. Examples include function calls that return an rvalue reference, and the array subscript, member and pointer to member expressions where the array or object is an rvalue reference.

A glvalue is an expression whose evaluation determines the identity of an object, bit-field, or function.

An rvalue is a prvalue or an xvalue.

Example

The following code block (again from Microsoft Documents) clearly states the difference between rvalues and lvalues.

// lvalues_and_rvalues2.cpp

int main()

{

int i, j, *p;

// Correct usage: the variable i is an lvalue and the literal 7 is a prvalue.

i = 7;

// Incorrect usage: The left operand must be an lvalue (C2106).`j * 4` is a prvalue.

7 = i; // C2106

j * 4 = 7; // C2106

// Correct usage: the dereferenced pointer is an lvalue.

*p = i;

// Correct usage: the conditional operator returns an lvalue.

((i < 3) ? i : j) = 7;

// Incorrect usage: the constant ci is a non-modifiable lvalue (C3892).

const int ci = 7;

ci = 9; // C3892

}

In simple terms: lvalues are the expressions that can be on both sides of an assignment operation, rvalues are the expressions that can only be on the right of an assignment operation.

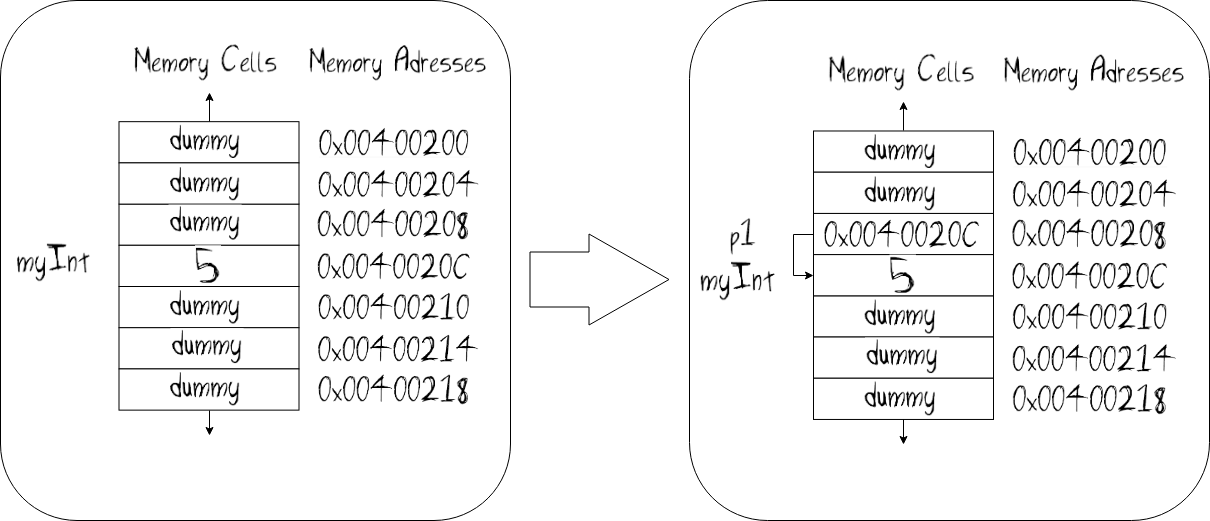

Pointers

Pointers are simply variables that points to a memory address which stores a value of type as the same as pointer’s. A pointer is declared with the asterisk symbol before variable name(identifier). The following code block shows the example pointer declaration and assignment.

int myInt = 5;

int *p1 = myInt;

In the following image the memory and variables is shown after 1st and 2nd line of code is executed.

References

References are like pointers. It stores the memory address of the object where it is stored. The difference of reference from pointer is: while pointers can refer another object after initialization, the object a refence refers can not change after initialization.

There are two kinds of references:

- lvalue references: They refer to a named variable. The & operator signifies an lvalue reference

- rvalue references: They refer to a temporary object. The && operator signifies either an rvalue reference.

Lvalue Reference Declarator

Lvalue reference like assigning another name for a variable. For example:

int x = 5;

int & y = x;

In the previous code block:

- Firstly an integer object is created with the identifier x. Let’s say x is stored at the memory address 0x004004AC.

- Then an lvalue reference with identifier name y is created which refers to the same memory cell (0x004004AC) which 5 value is stored.

Now i can access the value in memory cell 0x004004AC both via x and y. They modify the same cell.

Example

The following code block shows the use of lvalue reference declarator.

// compiled with: Visual Studio 2017 (v141)

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

struct Person

{

char* Name;

short Age;

};

int main()

{

// Declare a Person object.

Person myFriend;

// Declare a reference to the Person object.

Person& rFriend = myFriend;

// Set the fields of the Person object.

// Updating either variable changes the same object.

rFriend.Name = (char *)"Bill";

myFriend.Age = 40;

// Print the fields of the Person object to the console.

cout << "myFriend: " << myFriend.Name << " is " << myFriend.Age << endl;

cout << "rFriend: " << rFriend.Name << " is " << rFriend.Age << endl;

/* OUTPUT:

myFriend: Bill is 40

rFriend: Bill is 40

*/

// Create another Person object.

Person hisFriend;

hisFriend.Name = (char *)"George";

hisFriend.Age = 25;

// Assign lvalue reference to another object and see what it actually does

rFriend = hisFriend;

cout << "myFriend: " << myFriend.Name << " is " << myFriend.Age << endl;

cout << "rFriend: " << rFriend.Name << " is " << rFriend.Age << endl;

cout << "hisFriend: " << hisFriend.Name << " is " << hisFriend.Age << endl;

/* OUTPUT:

myFriend: George is 25

rFriend: George is 25

hisFriend: George is 25

*/

rFriend.Name = (char *)"Alice";

rFriend.Age = 28;

cout << "myFriend: " << myFriend.Name << " is " << myFriend.Age << endl;

cout << "rFriend: " << rFriend.Name << " is " << rFriend.Age << endl;

cout << "hisFriend: " << hisFriend.Name << " is " << hisFriend.Age << endl;

/* OUTPUT:

myFriend: Alice is 28

rFriend: Alice is 28

hisFriend: George is 25

*/

// It just assigned the values of the new object to referenced object

// Try it again with changing hisFriend's fields

rFriend = hisFriend;

cout << "myFriend: " << myFriend.Name << " is " << myFriend.Age << endl;

cout << "rFriend: " << rFriend.Name << " is " << rFriend.Age << endl;

cout << "hisFriend: " << hisFriend.Name << " is " << hisFriend.Age << endl;

/* OUTPUT:

myFriend: George is 25

rFriend: George is 25

hisFriend: George is 25

*/

hisFriend.Name = (char *)"Marx";

hisFriend.Age = 35;

cout << "myFriend: " << myFriend.Name << " is " << myFriend.Age << endl;

cout << "rFriend: " << rFriend.Name << " is " << rFriend.Age << endl;

cout << "hisFriend: " << hisFriend.Name << " is " << hisFriend.Age << endl;

/* OUTPUT:

myFriend: George is 25

rFriend: George is 25

hisFriend: Marx is 35

*/

return 0;

}

Rvalue Reference Declarator

They hold reference to rvalue expressions. And declared as in the following example:

using namespace std;

struct Person

{

char* Name;

short Age;

};

int main()

{

// Lets create a person

Person p;

p.Name = (char *)"John";

p.Age = 24;

// Then create a lvalue reference to the person we created

Person & lRefP = p; // Correct

Person & lRefP = Person(); // Wrong. Lvalue reference can not refer to a temporary object.

// Both of the following rvalue referencing is correct

Person && rRefP = p; // Correct

Person && rRefP = Person(); //Correct

return 0;

}

So what is the purpose of referencing to temporary objects?

The main motivation behind this is about the inefficiency of returning complex objects in pre-C++11 versions. Let’s say we have the following function.

string concatStrings(string s1, string s2){

string totalString = ""; // A memory space is allocated for totalString variable

totalString = s1 + s2;

return totalString; // Then this total string variable is destroyed and a copy of it is returned.

}

In the function, a local variable is created, and a memory space is allocated for that variable. After that, when it is time to return the result of the concatenation operation, a copy of the string object is created with copy constructor and it is returned to where the function is called from.

Since there is redundant memory allocation process in this method, developers used to avoid returning complex objects before C++11. Instead they used pointers to avoid redundant copy process.

Then with the C++11 a new method, move and move constructor was introduced. I will be talking about this topic deeply in the following posts; so that, simply what it does is avoiding redundant copy when returning an object from a function. The ownership of the resource allocated for the local variable in the function is transferred to caller of the function with the help of rvalue referencing.